The Story Of The Argus A

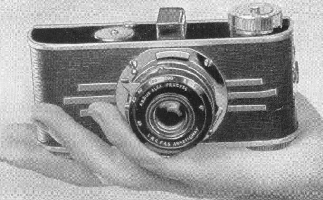

The concept of a compact 35mm camera was born in the early 1920s. It was then that Oscar Barnack of E. Leitz, Inc. developed a portable and accurate camera based on readily available 35mm film, then the standard for the movie industry. This camera, the Leica, took the world of amateur photography by storm from the day of its introduction in 1925 at the Leipzig Fair. Encrusted with knobs, dials, levers, and buttons, and not at all resembling any camera that came before it, the Leica was the ultimate gadget for the rich and stylish. Cameras were once large obtrusive objects that required considerable technical knowledge to operate, but with the Leica, amateurs could easily take high-quality, candid photos, then slip their cameras back into their jacket pockets. Still, the Leica’s exorbitant price, running up to $200, prevented it from finding its way into the common man’s hands.

In the early 1930s, the Leica drew the attention of Charles A. Verschoor during a trip to Europe. Verschoor was an American businessman who, along with other local businessmen, established a radio manufacturing business in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1931. International Radio Corporation (IRC) was responsible for the Kadette, the first AC/DC mantle radio on the market.

In the early 1930s, the Leica drew the attention of Charles A. Verschoor during a trip to Europe. Verschoor was an American businessman who, along with other local businessmen, established a radio manufacturing business in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1931. International Radio Corporation (IRC) was responsible for the Kadette, the first AC/DC mantle radio on the market.

Radio first began to mature in the late 1920s, and was considered a sound investment during the Depression era. For a one-time payment, your radio would play news, music, or entertainment daily for free! Using a relatively new plastic called Bakelite to mold the cases, IRC could cheaply produce radios and sell them for a decent profit.

The problem with radio manufacturing, however, was its reliance on the seasons. Customers, driven stir-crazy during the winter, would rush outside to meet the spring and, as a result, radio sales would dwindle until autumn forced consumers indoors again. Before the advent of air conditioning, people’s behavior was still tied to the weather, and their spending habits followed. To keep his factory and salesmen working all year, Verschoor searched for a product that could be cheaply manufactured and sold during the warmer half of the year. Amateur photography was starting to take hold in America, but was generally restricted to box-type cameras like the Kodak Brownie and the UniveX A. Verschoor decided to market an inexpensive Leica-inspired model and set his engineers to design one.

The Argus was designed to use the new Kodak 35mm daylight loading cartridge. This film cassette entered the market in late 1934 with the first camera designed to use it, the Kodak Retina. The new cartridge could be reloaded in a darkroom with surplus 35mm movie film, which was often plentiful and cheap. When Kodak introduced Kodachrome, the first color film, it was only available as rollfilm in the Kodak 35mm film cartridge, boosting this film format’s popularity. This cartridge was also the first that could easily be loaded into a camera in daylight. Such simplicity played a factor in the success of the Argus. The symbiotic relationship between Argus cameras and Kodak’s 35mm film cartridges boosted the popularity of both. The Argus A, and its more famous successor, the Argus C/C2/C3, are the primary reasons that the 35mm film format was established as firmly as it was, despite the plethora of similar formats that have been introduced and forced upon photographers in the last seventy years (UniveX 00, Kodak 828, 127, 126, 110, Disc, APS, etc…).

The Argus was designed to use the new Kodak 35mm daylight loading cartridge. This film cassette entered the market in late 1934 with the first camera designed to use it, the Kodak Retina. The new cartridge could be reloaded in a darkroom with surplus 35mm movie film, which was often plentiful and cheap. When Kodak introduced Kodachrome, the first color film, it was only available as rollfilm in the Kodak 35mm film cartridge, boosting this film format’s popularity. This cartridge was also the first that could easily be loaded into a camera in daylight. Such simplicity played a factor in the success of the Argus. The symbiotic relationship between Argus cameras and Kodak’s 35mm film cartridges boosted the popularity of both. The Argus A, and its more famous successor, the Argus C/C2/C3, are the primary reasons that the 35mm film format was established as firmly as it was, despite the plethora of similar formats that have been introduced and forced upon photographers in the last seventy years (UniveX 00, Kodak 828, 127, 126, 110, Disc, APS, etc…).

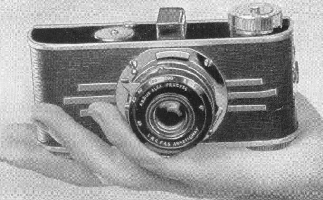

IRC’s engineers had extensive experience molding Bakelite and took advantage of this knowledge in designing the body of the Argus. Bakelite allowed the camera body to be cheaply decorated with a distinct Art Deco flair. Gustave Fassin, an engineer for IRC, is generally believed to have designed the Argus, though the patent is credited to Verschoor and makes no mention of Fassin.

The Argus, priced at only $12.50, was a success from its debut in early 1936; IRC later claimed to have sold 30,000 cameras in the first week alone. Prospects seemed so promising that Verschoor decided to give up radio manufacturing altogether and sold off the patent rights for the Kadette radio to IRC’s general sales manager, W. Keene Jackson, who went on to found the soon-defunct Kadette Radio Corporation. IRC changed its name from International Radio Corporation to International Research Corporation to reflect this redirection in corporate focus.

The Argus, priced at only $12.50, was a success from its debut in early 1936; IRC later claimed to have sold 30,000 cameras in the first week alone. Prospects seemed so promising that Verschoor decided to give up radio manufacturing altogether and sold off the patent rights for the Kadette radio to IRC’s general sales manager, W. Keene Jackson, who went on to found the soon-defunct Kadette Radio Corporation. IRC changed its name from International Radio Corporation to International Research Corporation to reflect this redirection in corporate focus.

In 1937, the Argus A was followed by the Argus AF and the Argus B, which were two variations on the same theme. The AF, at $15.00, had an infinitely adjustable focusing mount but the same shutter and lenses, while the B, at $25.00, had a higher quality Prontor II shutter imported from Germany. The B was dropped that same year because of lack of consumer interest and the AF was withdrawn from production in 1938, presumably to prepare for the introduction of the A2F.

Riding on the heels of this unparalleled success, IRC introduced other models, such as the unrelated Argus A3 and Argus C. Also designed by Gustave Fassin, the Argus C-type camera would become the bread and butter of the Argus line. Nicknamed “the brick” for its boxy appearance, it would stay in production until 1966—an unbelievable 28 years! This was a sturdy camera with a coupled rangefinder and a respectable f/3.5 Cintar lens, and it was IRC’s very successful attempt at entering the market of medium-cost cameras. Kodak, in response to IRC stealing its market, heavily modified one of its cameras to compete with the C3. This jury-rigged contraption became the Kodak 35RF, which still couldn’t match the C3 in either price or features.

To make amateur photography easier, in 1939 IRC introduced the Argus A2B (at $12.50) and the A2F (at $15.00). These were nearly identical to the Argus A and AF with only an integral extinction meter and exposure calculator added. With this “miraculous” device, the user didn’t need a light meter or any knowledge of photography to take a decent picture. Just look through the meter, add the film speed and lighting conditions to the calculator, and an assortment of f-stop/shutter speed combinations are suggested to produce a serviceable picture! The Argus A2F was discontinued in 1941, probably due to the effort involved in manufacturing the focusing mount. Production of the A2B, with minor changes, continued until 1950.

To take advantage of the recently invented flashbulb, Verschoor decided to produce a model of the Argus that could use a flash, thus giving life to the Argus AA in 1940. The Argus A adapted poorly to the addition of a flash, however, as many of the components of the flash mechanism were carefully assembled by hand. The shutter had to be completely redesigned and the two-position focus gave way to “fixed focus.” The lens shrank in size to f/6.3, probably to make room for flash components. This weak adaptation did not last long, and the AA was dropped in 1942. By then, International Research Corporation had changed its name to Argus International Industries, Inc. in order to identify the company with its product.

To take advantage of the recently invented flashbulb, Verschoor decided to produce a model of the Argus that could use a flash, thus giving life to the Argus AA in 1940. The Argus A adapted poorly to the addition of a flash, however, as many of the components of the flash mechanism were carefully assembled by hand. The shutter had to be completely redesigned and the two-position focus gave way to “fixed focus.” The lens shrank in size to f/6.3, probably to make room for flash components. This weak adaptation did not last long, and the AA was dropped in 1942. By then, International Research Corporation had changed its name to Argus International Industries, Inc. in order to identify the company with its product.

Then came December 7th, 1941. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States began to mobilize for war. It is impossible to underestimate the effect that World War II had on American industrial capability, methods, and design. Massive government contracts were awarded to every American industry. Unheard-of sums of government cash were dumped into military-oriented research and development. New materials and techniques of manufacture that would never have been considered before suddenly became popular.

As an American manufacturer of optical equipment, the Argus corporation benefited from this economic spurt in many ways. It began to produce a variety of optical equipment for military use, like the Argus Observation Scope, retained with others in the Argus line of products after the war. In addition, the US Army put in an order for 50,000 C3 cameras to sell in its Post Exchanges. The military showed its appreciation for the Argus corporation’s contribution to the war effort by awarding the company the Army-Navy E Award for production a total of five times.

The US emerged from World War II a manufacturing powerhouse, one of only two superpowers, and the only country on earth with nuclear weapons. Because of these and other factors, the patriotic American consumer became a different person as well. Due to economic depression and wartime rationing, consumers had been restrained for the previous fifteen years. The post-war economic boom let them know that they didn’t have to settle for second best any more. The modern design movement, greatly influenced by new materials and mass production techniques conceived during the war, began to create inexpensive, stylish American products of decent quality, and the public went mad for them. In response to the wave of nationalism that was sweeping the country, Argus dropped the “International” in its name in 1945 and became simply Argus Industries, Inc.

The US emerged from World War II a manufacturing powerhouse, one of only two superpowers, and the only country on earth with nuclear weapons. Because of these and other factors, the patriotic American consumer became a different person as well. Due to economic depression and wartime rationing, consumers had been restrained for the previous fifteen years. The post-war economic boom let them know that they didn’t have to settle for second best any more. The modern design movement, greatly influenced by new materials and mass production techniques conceived during the war, began to create inexpensive, stylish American products of decent quality, and the public went mad for them. In response to the wave of nationalism that was sweeping the country, Argus dropped the “International” in its name in 1945 and became simply Argus Industries, Inc.

This did not bode well for the A2B, the only Argus A-type camera manufactured at the end of the war. Designed to be affordable for Depression-era America, the A2B didn’t offer a rangefinder or flash capability, and had only a two-position focus. The f/4.5 lens that seemed so fast before the war was now slower than lenses available on other cameras. In addition, the art deco styling that made the Argus so smart at its introduction now seemed dowdy and old fashioned. With a different shutter and fluoride-coated lenses, the A2B was retained in the Argus line as a low-end camera, suitable for college students and amateurs.

No economic boom lasts forever, though, and the recession of 1948-49 hit all of America hard. Argus shareholders needed a scapegoat, and in 1949, after a brief power struggle, the shareholders brought in Robert E. Lewis to head the company. Lewis and his boys decided to phase out every old line of cameras, including the Argus A2B, and began to design new ones. The only camera saved from the slaughter was the popular C3. These were the ignoble circumstances under which the Argus A2B left the company, now again renamed Argus Cameras, Inc.

This was not the end for the Argus A-type camera, however. Possibly to fill in the gap for a low-cost camera while other cameras were being developed, Argus introduced the FA, which was another flash version of the A. But the FA only lasted from 1950 to 1951. Its successor, the totally redesigned and restyled A4, arrived on dealers’ shelves in 1953 and became the new low-cost representative of the Argus line. The A4 was a completely new design and shared nothing but a name with its predecessors.

This was not the end for the Argus A-type camera, however. Possibly to fill in the gap for a low-cost camera while other cameras were being developed, Argus introduced the FA, which was another flash version of the A. But the FA only lasted from 1950 to 1951. Its successor, the totally redesigned and restyled A4, arrived on dealers’ shelves in 1953 and became the new low-cost representative of the Argus line. The A4 was a completely new design and shared nothing but a name with its predecessors.

One can see that the Argus A was very much a product of the times, and it was once those times changed that the age of the Argus A ended.

All did not go well with Argus Cameras, Inc. after the demise of the A/A2 line. Higher quality and cheaper cameras from West Germany and Japan began to flood the market, and, as a result, the company started hemorrhaging money. Argus enjoyed only a modest success with the C4/C44, which was intended to become the new workhorse of the Argus line. Successive attempts to update the C3 were not well-received by the consumer, who preferred the original to the updated models. The company was passed around from owner to owner.

Seventy years since the introduction of the Argus A (1936-2006), Argus Camera Company, LLC is still around today and you can visit them online at www.arguscamera.com. They produce an assortment of 35mm and digital cameras, webcams, and digital video cameras. Unfortunately, they no longer offer the Argus A.

|

In the early 1930s, the Leica drew the attention of Charles A. Verschoor during a trip to Europe. Verschoor was an American businessman who, along with other local businessmen, established a radio manufacturing business in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1931. International Radio Corporation (IRC) was responsible for the Kadette, the first AC/DC mantle radio on the market.

In the early 1930s, the Leica drew the attention of Charles A. Verschoor during a trip to Europe. Verschoor was an American businessman who, along with other local businessmen, established a radio manufacturing business in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1931. International Radio Corporation (IRC) was responsible for the Kadette, the first AC/DC mantle radio on the market.

The Argus was designed to use the new Kodak 35mm daylight loading cartridge. This film cassette entered the market in late 1934 with the first camera designed to use it, the Kodak Retina. The new cartridge could be reloaded in a darkroom with surplus 35mm movie film, which was often plentiful and cheap. When Kodak introduced Kodachrome, the first color film, it was only available as rollfilm in the Kodak 35mm film cartridge, boosting this film format’s popularity. This cartridge was also the first that could easily be loaded into a camera in daylight. Such simplicity played a factor in the success of the Argus. The symbiotic relationship between Argus cameras and Kodak’s 35mm film cartridges boosted the popularity of both. The Argus A, and its more famous successor, the Argus C/C2/C3, are the primary reasons that the 35mm film format was established as firmly as it was, despite the plethora of similar formats that have been introduced and forced upon photographers in the last seventy years (UniveX 00, Kodak 828, 127, 126, 110, Disc, APS, etc…).

The Argus was designed to use the new Kodak 35mm daylight loading cartridge. This film cassette entered the market in late 1934 with the first camera designed to use it, the Kodak Retina. The new cartridge could be reloaded in a darkroom with surplus 35mm movie film, which was often plentiful and cheap. When Kodak introduced Kodachrome, the first color film, it was only available as rollfilm in the Kodak 35mm film cartridge, boosting this film format’s popularity. This cartridge was also the first that could easily be loaded into a camera in daylight. Such simplicity played a factor in the success of the Argus. The symbiotic relationship between Argus cameras and Kodak’s 35mm film cartridges boosted the popularity of both. The Argus A, and its more famous successor, the Argus C/C2/C3, are the primary reasons that the 35mm film format was established as firmly as it was, despite the plethora of similar formats that have been introduced and forced upon photographers in the last seventy years (UniveX 00, Kodak 828, 127, 126, 110, Disc, APS, etc…).

The Argus, priced at only $12.50, was a success from its debut in early 1936; IRC later claimed to have sold 30,000 cameras in the first week alone. Prospects seemed so promising that Verschoor decided to give up radio manufacturing altogether and sold off the patent rights for the Kadette radio to IRC’s general sales manager, W. Keene Jackson, who went on to found the soon-defunct Kadette Radio Corporation. IRC changed its name from International Radio Corporation to International Research Corporation to reflect this redirection in corporate focus.

The Argus, priced at only $12.50, was a success from its debut in early 1936; IRC later claimed to have sold 30,000 cameras in the first week alone. Prospects seemed so promising that Verschoor decided to give up radio manufacturing altogether and sold off the patent rights for the Kadette radio to IRC’s general sales manager, W. Keene Jackson, who went on to found the soon-defunct Kadette Radio Corporation. IRC changed its name from International Radio Corporation to International Research Corporation to reflect this redirection in corporate focus.

To take advantage of the recently invented flashbulb, Verschoor decided to produce a model of the Argus that could use a flash, thus giving life to the Argus AA in 1940. The Argus A adapted poorly to the addition of a flash, however, as many of the components of the flash mechanism were carefully assembled by hand. The shutter had to be completely redesigned and the two-position focus gave way to “fixed focus.” The lens shrank in size to f/6.3, probably to make room for flash components. This weak adaptation did not last long, and the AA was dropped in 1942. By then, International Research Corporation had changed its name to Argus International Industries, Inc. in order to identify the company with its product.

To take advantage of the recently invented flashbulb, Verschoor decided to produce a model of the Argus that could use a flash, thus giving life to the Argus AA in 1940. The Argus A adapted poorly to the addition of a flash, however, as many of the components of the flash mechanism were carefully assembled by hand. The shutter had to be completely redesigned and the two-position focus gave way to “fixed focus.” The lens shrank in size to f/6.3, probably to make room for flash components. This weak adaptation did not last long, and the AA was dropped in 1942. By then, International Research Corporation had changed its name to Argus International Industries, Inc. in order to identify the company with its product.

The US emerged from World War II a manufacturing powerhouse, one of only two superpowers, and the only country on earth with nuclear weapons. Because of these and other factors, the patriotic American consumer became a different person as well. Due to economic depression and wartime rationing, consumers had been restrained for the previous fifteen years. The post-war economic boom let them know that they didn’t have to settle for second best any more. The modern design movement, greatly influenced by new materials and mass production techniques conceived during the war, began to create inexpensive, stylish American products of decent quality, and the public went mad for them. In response to the wave of nationalism that was sweeping the country, Argus dropped the “International” in its name in 1945 and became simply Argus Industries, Inc.

The US emerged from World War II a manufacturing powerhouse, one of only two superpowers, and the only country on earth with nuclear weapons. Because of these and other factors, the patriotic American consumer became a different person as well. Due to economic depression and wartime rationing, consumers had been restrained for the previous fifteen years. The post-war economic boom let them know that they didn’t have to settle for second best any more. The modern design movement, greatly influenced by new materials and mass production techniques conceived during the war, began to create inexpensive, stylish American products of decent quality, and the public went mad for them. In response to the wave of nationalism that was sweeping the country, Argus dropped the “International” in its name in 1945 and became simply Argus Industries, Inc.

This was not the end for the Argus A-type camera, however. Possibly to fill in the gap for a low-cost camera while other cameras were being developed, Argus introduced the FA, which was another flash version of the A. But the FA only lasted from 1950 to 1951. Its successor, the totally redesigned and restyled A4, arrived on dealers’ shelves in 1953 and became the new low-cost representative of the Argus line. The A4 was a completely new design and shared nothing but a name with its predecessors.

This was not the end for the Argus A-type camera, however. Possibly to fill in the gap for a low-cost camera while other cameras were being developed, Argus introduced the FA, which was another flash version of the A. But the FA only lasted from 1950 to 1951. Its successor, the totally redesigned and restyled A4, arrived on dealers’ shelves in 1953 and became the new low-cost representative of the Argus line. The A4 was a completely new design and shared nothing but a name with its predecessors.